Script / Documentation

Welcome to Just Facts Academy, where you learn how to research like a genius.

Remember, you don’t have to be an Einstein to be a great researcher. You simply need to put in the effort and apply the 7 Standards of Credibility that we share in this video series.

Today’s lesson: Primary Sources.

Let’s define this standard, explain why it’s important, and show you how to apply it in your own research.

So what exactly is a primary source? I like how the Ithaca College Library website puts it: “A primary source provides direct or firsthand evidence….”[1]

A news article, an award-winning book, even Wikipedia may accurately portray the truth, but if it cites information from another source, then it’s not the primary source for that information.

This is extremely important to recognize. Why?

Well, whether intentionally or not, secondary sources often reflect someone’s interpretation of the facts—instead of the actual facts. A secondary source usually filters and paraphrases information while leaving some in—and leaving some out.

This can cause all sorts of problems. Remember that childhood game “Telephone”? How often did that original phrase make it to the last person without significant distortions?

And that assumes everyone is passing information with the best intentions and would never be dishonest.

Secondary sources typically have much less space to convey the facts and often leave out important caveats revealed by the original sources. This is a huge reason why it’s so crucial to access the primary source.

And one more thing, make sure the source is credible. Though a tweet from an activist at a political rally can provide firsthand evidence—and thus be a primary source—that does not mean they should be blindly believed. Credible sources prove what they say by providing conclusive evidence.

Are you ready for an example? This one’s pretty ridiculous—but it reveals how the failure to use primary sources can lead you to believe complete nonsense.

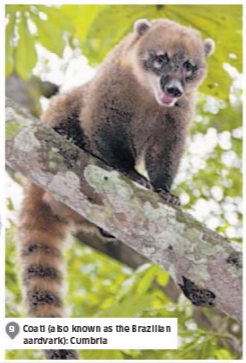

Have you ever heard of the Brazilian aardvark? No, it’s not a newly discovered species. Somebody fabricated this name to describe a raccoon-like creature that’s actually called a “coati.” Then he put the name on Wikipedia as a joke.[2] [3]

Well, no one caught it. And in the next few years, dozens of websites began calling this creature a “Brazilian aardvark.”[4] This includes media outlets like Time magazine,[5] Scientific American,[6] the London Telegraph,[7] The Independent,[8] and even a book published by the University of Chicago.[9]

When this fictional name was first posted on Wikipedia, there was, of course, no source for it. But after other websites used Wikipedia as their source, Wikipedia editors could now provide a source for this bogus claim: one of the very same sources that took it from Wikipedia.[10] [11]

See how easily misinformation can spread when people trust secondary sources?

Now, it’s not a big deal if you think a Brazilian aardvark exists—but when it comes to important issues—it’s vital to go to the primary source, so you don’t get fooled.

One of those issues is sexual violence.

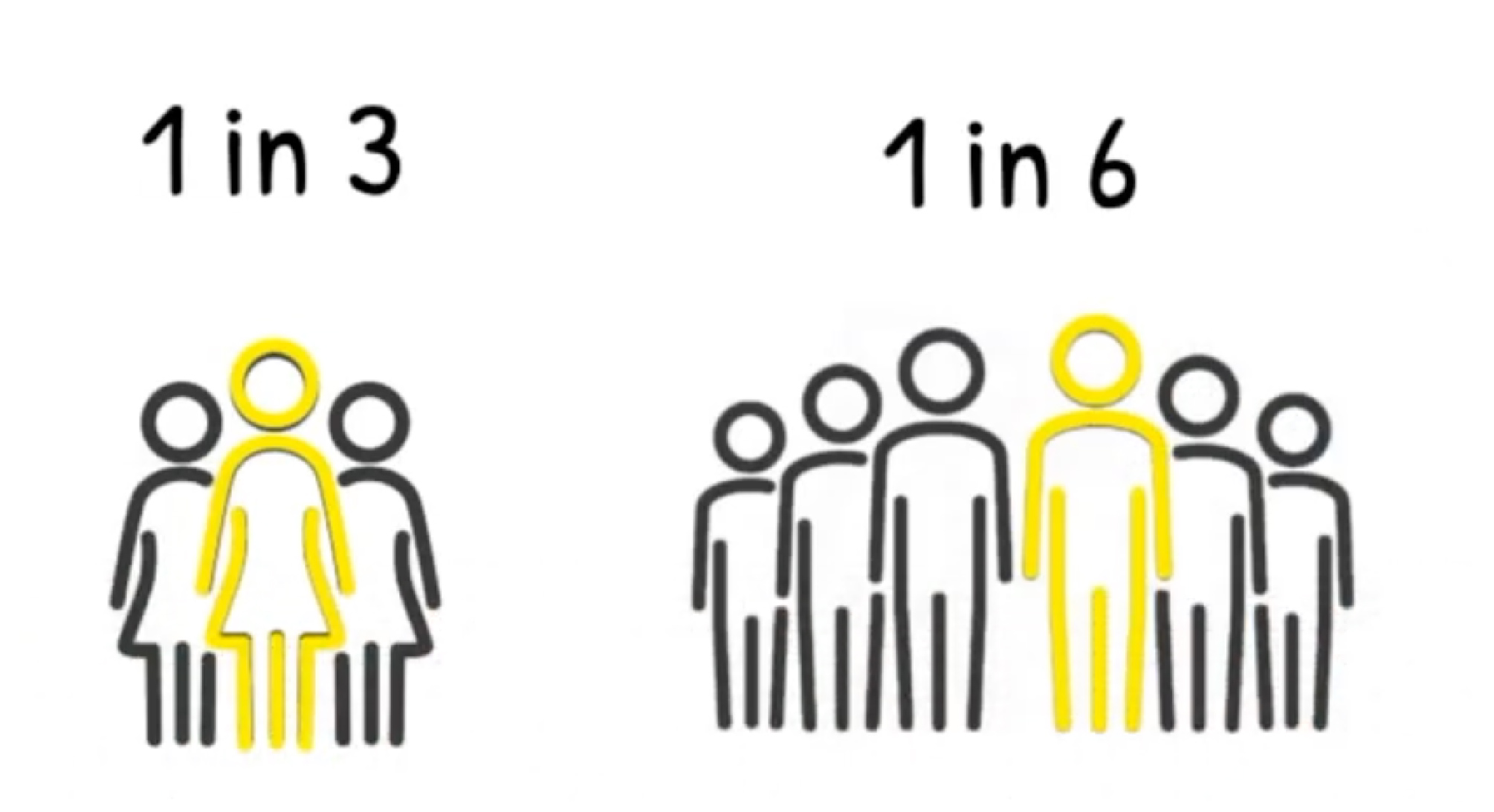

A very common claim concerning this horrible crime is that “one in three women and one in six men will experience some form of sexual violence in their lifetime.”[12]

This statistic comes from a study published by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control in 2014.[13] And everyone from major media outlets to U.S. senators have quoted it.[14] [15] [16] [17] [18]

However, the definition of sexual violence in this CDC report could easily lead you to the wrong impression. This is because it includes scenarios like an unwanted kiss and consensual sex after someone tells you a lie or makes a false promise.[19] [20]

You would never know this from the vast majority of secondary sources that have cited this statistic, like media outlets and senators—or even if you read the CDC’s entire 18-page report. You can only find it in a file of supplementary information attached to the report.[21] [22] That is the primary source for these facts.

As you can see, you can easily be misled if you don’t access the primary source.

So, how can you apply this standard in your research?

First, learn to identify what is a primary source and what is not. Common primary sources are government reports, datasets, papers in academic journals, uncut videos, and complete transcripts.

Bear in mind, something can be a primary source for one fact and a secondary source for another. Again, if a source relies on another source or does not provide documented evidence, it is not the primary source for that information.

Second, be ready to dig. The internet has made primary sources far more available than any time in human history. But finding them sometimes requires digging back from one source to another, to another, until you finally reach that pot of gold. When you do, you may be surprised how different it is from the secondary sources that you dug through.

Third, don’t give up. Internet searches often yield a lot of shoddy content. Don’t stop at the first 10 results. Focus your searches to find exactly what you’re looking for—instead of what some big corporation deems reliable.

You can sometimes cut down on the clutter from search engines by using Google Scholar or an academic database at your local library or school.

Fourth, once you get the primary source, make sure you get the whole story. Learn how the data was collected: Where? Who? What questions were asked?

Most studies contain a section called “limitations.” Read it and consider how your conclusions could be affected.

Now that you know about primary sources, don’t settle for anything less when dealing with important matters. Instead, dig to that primary source—and apply the rest of Just Facts’ Standards of Credibility—so you can research like a genius.

Footnotes

[1] Webpage: “Research 101: Primary vs. Secondary.” Ithaca College Library. Accessed June 12, 2021 at <library.ithaca.edu>

A primary source provides direct or firsthand evidence about an event, object, person, or work of art. Primary sources include historical and legal documents, eyewitness accounts, results of experiments, statistical data, pieces of creative writing, audio and video recordings, speeches, and art objects. Interviews, surveys, fieldwork, and Internet communications via email, blogs, listservs, and newsgroups are also primary sources. In the natural and social sciences, primary sources are often empirical studies—research where an experiment was performed, or a direct observation was made. The results of empirical studies are typically found in scholarly articles or papers delivered at conferences.

[2] Article: “How a Raccoon Became an Aardvark.” By Eric Randall. The New Yorker, May 19, 2014. <www.newyorker.com>

In July of 2008, Dylan Breves, then a seventeen-year-old student from New York City, made a mundane edit to a Wikipedia entry on the coati. The coati, a member of the raccoon family, is “also known as … a Brazilian aardvark,” Breves wrote. He did not cite a source for this nickname, and with good reason: he had invented it. He and his brother had spotted several coatis while on a trip to the Iguacu Falls, in Brazil, where they had mistaken them for actual aardvarks.

“I don’t necessarily like being wrong about things,” Breves told me. “So, sort of as a joke, I slipped in the ‘also known as the Brazilian aardvark’ and then forgot about it for awhile.”

Adding a private gag to a public Wikipedia page is the kind of minor vandalism that regularly takes place on the crowdsourced Web site. When Breves made the change, he assumed that someone would catch the lack of citation and flag his edit for removal.

Over time, though, something strange happened: the nickname caught on. About a year later, Breves searched online for the phrase “Brazilian aardvark.” Not only was his edit still on Wikipedia, but his search brought up hundreds of other Web sites about coatis. … Breves’s role in all this seems clear: a Google search for “Brazilian aardvark“ will return no mentions before Breves made the edit, in July, 2008.

[3] Search: “brazilian aardvark”. Google, June 12, 2021. Date delimited to before June 1, 2008. <www.google.com>

NOTE: This search produced 2 results, both of which were later edits to webpages that were created before June 1, 2008.

[4] Search: “brazilian aardvark”. Google, June 12, 2021. Date delimited from 5/31/2008 to 5/1/2014. <www.google.com>

NOTE: This search produced more than two dozen unique results that naively described a coati as a “Brazilian Aardvark.”

[5] Photo: “Wild Fire.” Time, September 20, 2013. <time.com>

“A coati, or Brazilian aardvark, jumps through burning hoops during a show called ‘The Caravan of Wonders’ at the National Circus in Kiev.”

[6] Blog post: “Brazil Plans to Clone Its Endangered Species.” By John R. Platt. Scientific American, November 14, 2012. <blogs.scientificamerican.com>

The scientists have already spent the past two years collecting 420 genetic samples for the species—mostly from dead specimens found in the Cerrado savanna region—and are now waiting for legal authorization to start the cloning. If they receive government approval, the species they’ll be working with would include the … Brazilian aardvark, also known locally as coati (Nasua nasua)….

[7] Article: “Scorpions, Brazilian Aardvarks and Wallabies All Found Living Wild in UK, Study Finds.” By Ben Leach. The Telegraph, June 1, 2010. <www.telegraph.co.uk>

“They may not be animals synonymous with the British countryside, but scorpions, Brazilian aardvarks and wallabies have all been found living wild in the UK.”

[8] Article: “From Wallabies to Chipmunks, the Exotic Creatures Thriving in the UK.” By Jonathan Brown. The Independent, June 21, 2010. Page 8. <issuu.com>

A report published today reveals that scorpions, aardvarks and even wallabies are among the creatures living alongside the UK’s traditional fauna of hedgehogs, badgers and squirrels. …

Coati (also known as the Brazilian aardvark): Cumbria |

[9] The Book of Barely Imagined Beings: A 21st Century Bestiary. By Caspar Henderson. University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Page 10: “The coati, also known as the hog-nosed coon, the snookum bear or the Brazilian aardvark, is a kind of raccoon.”

[10] Webpage: “Coati: Difference Between Revisions.” Wikipedia. Accessed June 12, 2021 at <en.wikipedia.org>

Revision as of 15:24, 8 May 2014

Coatis, genera Nasua and Nasuella, also known as coatimundi … [1][2] Brazilian aardvark,[3] Mexican tejón, cholugo, or moncún, hog-nosed coons,[4] and other names, are members of the raccoon family (Procyonidae). …

[3] Leach, Ben (21 June 2010) Scorpions, Brazilian aardvarks and wallabies all found living wild in UK, study finds. telegraph.co.uk

[11] Article: “Scorpions, Brazilian Aardvarks and Wallabies All Found Living Wild in UK, Study Finds.” By Ben Leach. The Telegraph, June 1, 2010. <www.telegraph.co.uk>

“They may not be animals synonymous with the British countryside, but scorpions, Brazilian aardvarks and wallabies have all been found living wild in the UK.”

[12] Search: (1 OR one) in (3 OR three) women (6 OR six) men “sexual violence”. Google, June 12, 2021. Date delimited from 1/1/2014 to 1/1/2021. <www.google.com>

NOTE: This search produced dozens of results that repeat this statistic.

[13] Report: “Prevalence and Characteristics of Sexual Violence, Stalking, and Intimate Partner Violence Victimization—National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, United States, 2011.” By Matthew J. Breiding and others. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention, September 5, 2014. <www.cdc.gov>

“In the United States, an estimated 19.3% of women and 1.7% of men have been raped during their lifetimes…. An estimated 43.9% of women and 23.4% of men experienced other forms of sexual violence during their lifetimes, including being made to penetrate, sexual coercion, unwanted sexual contact, and noncontact unwanted sexual experiences.”

[14] Article: “ ‘Women’s Lives in Danger’: Government Shutdown Holds Up Funds for Sexual Violence Survivors.” By Elizabeth Chuck. NBC News, January 3, 2019. <www.nbcnews.com>

“About one in three women and one in six men in the U.S. experience some form of contact sexual violence in their lifetime, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.”

[15] Article: “In First Presidential Election Post-Me Too, Survivors of Sexual Violence Largely Invisible.” By Alia E. Dastagir. USA Today, October 21, 2020. <www.usatoday.com>

“In the United States, one in three women experiences some form of sexual violence in her lifetime, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—those are millions of survivors who have watched as the first presidential election post-Me Too has rendered them largely invisible.”

[16] Article: “Sexism Isn’t Just Unfair; It Makes Women Sick, Study Suggests.” By Catherine Harnois (Professor of Sociology, Wake Forest University) and Joao Luiz Bastos (Associate Professor of Public Health, Wake Forest University). The Conversation, May 4, 2018. <theconversation.com>

“Social science research takes a different form than protests, but paints a similar picture. A recent report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 1 in 3 women and 1 in 6 men in the U.S. experience contact sexual violence in their lifetime. Contact sexual violence is defined as being made to have sexual intercourse with someone else, being sexually coerced, or having unwanted sexual contact.”

[17] Hearing: “Nomination of the Honorable Brett M. Kavanaugh to be an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States (Day 5).” U.S. Senate, Judiciary Committee, September 27, 2018. <www.judiciary.senate.gov>

Time marker 35:27: Senator Dianne Feinstein (D–CA): “Sexual violence is a serious problem, and one that largely goes unseen. In the United States, it’s estimated by the Centers for Disease Control one in three women and one in six men will experience some form of sexual violence in their lifetime.”

[18] Hearing: “Nomination of the Honorable Brett M. Kavanaugh to be an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States (Day 6).” U.S. Senate, Judiciary Committee, September 28, 2018. <www.judiciary.senate.gov>

Time marker 3:30:07: Senator Cory Booker (D–NJ): “Sexual violence is a serious problem, and one that largely goes unseen. In the United States, it’s estimated by the Centers for Disease Control one in three women and one in six men will experience some form of sexual violence in their lifetime.”

[19] Report: “Prevalence and Characteristics of Sexual Violence, Stalking, and Intimate Partner Violence Victimization—National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, United States, 2011.” By Matthew J. Breiding and others. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention, September 5, 2014. <www.cdc.gov>

Page 3: “The questionnaire included behaviorally specific questions that assessed being a victim of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence over the respondent’s lifetime and during the 12 months before interview. A list of the verbatim questions used in the 2011 survey can be found at <stacks.cdc.gov>.”

[20] “National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) 2011 Victimization Questions.” U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, September 5, 2014. <stacks.cdc.gov>

Page 3:

Sexual Violence Intro: Women and men may experience unwanted and uninvited sexual situations by strangers or people they know well, such as a romantic or sexual partner, friend, teacher, coworker, supervisor, or family member. Your answers will help us learn how often these things happen. Some of the language we use is explicit, but it is important that I ask the questions this way so that you are clear about what I mean. The questions we ask are detailed and some people may find them upsetting. The information you are providing will be kept private. You can skip questions you don’t want to answer and you can stop at any time.

I’m going to ask you about different types of unwanted sexual situations. In general, these are: unwanted sexual situations that did NOT involve touching and situations that DID involve touching. I will also ask you about situations in which you were unable to provide consent to sex because of alcohol or drugs, and about your experiences with unwanted sex that happened when someone used physical force or verbal pressure.

How many people have ever...

• exposed their sexual body parts to you, flashed you, or masturbated in front of you?

• made you show your sexual body parts to them when you didn’t want it to happen?

• made you look at or participate in sexual photos or movies?

• verbally harassed you while you were in a public place in a way that made you feel unsafe?

• kissed you in a sexual way when you didn’t want it to happen?

• fondled, groped, grabbed, or touched you in a way that made you feel unsafe?

Page 4:

Intro: Sometimes unwanted sexual contact happens after a person is pressured in a nonphysical way.

How many people have you had vaginal, oral, or anal sex with after they pressured you by…

• doing things like telling you lies, making promises about the future they knew were untrue, threatening to end your relationship, or threatening to spread rumors about you?

• wearing you down by repeatedly asking for sex, or showing they were unhappy?

• using their influence or authority over you, for example, your boss or your teacher?

[21] Report: “Prevalence and Characteristics of Sexual Violence, Stalking, and Intimate Partner Violence Victimization—National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, United States, 2011.” By Matthew J. Breiding and others. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention, September 5, 2014. <www.cdc.gov>

Page 3: “The questionnaire included behaviorally specific questions that assessed being a victim of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence over the respondent’s lifetime and during the 12 months before interview. A list of the verbatim questions used in the 2011 survey can be found at <stacks.cdc.gov>.”

[22] “National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) 2011 Victimization Questions.” U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, September 5, 2014. <stacks.cdc.gov>

Page 3:

Sexual Violence Intro: Women and men may experience unwanted and uninvited sexual situations by strangers or people they know well, such as a romantic or sexual partner, friend, teacher, coworker, supervisor, or family member. Your answers will help us learn how often these things happen. Some of the language we use is explicit, but it is important that I ask the questions this way so that you are clear about what I mean. The questions we ask are detailed and some people may find them upsetting. The information you are providing will be kept private. You can skip questions you don’t want to answer and you can stop at any time.

I’m going to ask you about different types of unwanted sexual situations. In general, these are: unwanted sexual situations that did NOT involve touching and situations that DID involve touching. I will also ask you about situations in which you were unable to provide consent to sex because of alcohol or drugs, and about your experiences with unwanted sex that happened when someone used physical force or verbal pressure.

How many people have ever...

• exposed their sexual body parts to you, flashed you, or masturbated in front of you?

• made you show your sexual body parts to them when you didn’t want it to happen?

• made you look at or participate in sexual photos or movies?

• verbally harassed you while you were in a public place in a way that made you feel unsafe?

• kissed you in a sexual way when you didn’t want it to happen?

• fondled, groped, grabbed, or touched you in a way that made you feel unsafe?

Page 4:

Intro: Sometimes unwanted sexual contact happens after a person is pressured in a nonphysical way.

How many people have you had vaginal, oral, or anal sex with after they pressured you by…

• doing things like telling you lies, making promises about the future they knew were untrue, threatening to end your relationship, or threatening to spread rumors about you?

• wearing you down by repeatedly asking for sex, or showing they were unhappy?

• using their influence or authority over you, for example, your boss or your teacher?